Ajahn Amaro [Excerpts from “Small Boat, Great Mountain”]

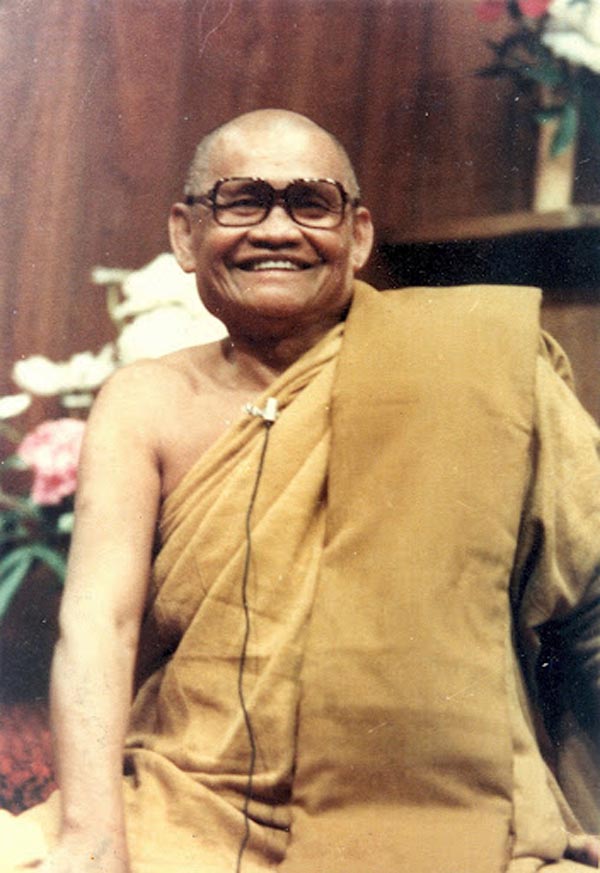

One of the topics that Ajahn Chah most liked to emphasise was the principle of nonabiding. During the brief two years that I was with him in Thailand, he spoke about it many times. In various ways he tried to convey that nonabiding was the essence of the path, a basis of peace, and a doorway into the world of freedom.

The Limitations of the Conditioned Mind

During the summer of 1981, Ajahn Chah gave a very significant teaching to Ajahn Sumedho on the liberating quality of nonabiding. Ajahn Sumedho had been in England for a few years when a letter arrived from Thailand. Even though Ajahn Chah could read and write, he rarely did. In fact, he hardly wrote anything, and he never wrote letters. The message began with a note from a fellow Western monk. It said: “Well, Ajahn Sumedho, you are not going to believe this, but Luang Por decided he wanted to write you a letter, so he asked me to take his dictation.” The message from Ajahn Chah was very brief, and this is what it said: “Whenever you have feelings of love or hate for anything whatsoever, these will be your aides and partners in building pārami (perfection of core virtues, including: honesty, generosity, proper conduct, etc). The Buddha-Dharma is not to be found in moving forwards, nor in moving backwards, nor in standing still. This, Sumedho, is your place of nonabiding.”

A few weeks later, Ajahn Chah had a stroke and became unable to speak, walk, or move. His verbal teaching career was over. This letter contained his final instructions.

During my time at his monastery in Thailand, Ajahn Chah would sit on a wicker bench in the open area underneath his hut and receive visitors from ten o’clock in the morning until late at night. Every day. Sometimes until two or three in the morning.

Amongst the many ways in which he would convey the teachings, Ajahn Chah would put various conundrums out to the listeners, queries or puzzles designed to frustrate and then break through the limitations of the conditioned mind. He would ask such questions as: “Is this stick long or short?” “Where did you come from and where are you going?” Or, as here, “If you can’t go forwards and you can’t go back and you can’t stand still, where do you go?” And when he’d put forth these questions, he’d have a look on his face like a cobra.

Some of the more courageous responders would try a reasonable answer:

“Go to the side?”

“Nope, can’t go to the side either.”

“Up or down?” “He would keep pushing people as they struggled to come up with a “right” answer. The more creative or clever they got, the more he would make them squirm: “No, no! That’s not it.”

Ajahn Chah was trying to push his inquirers up against the limitations of the conditioned mind, in hopes of opening up a space for the unconditioned to shine through. The principle of nonabiding is exceedingly frustrating to the conceptual/thinking mind, because that mind has built up such an edifice out of “me” and “you,” out of “here” and “there,” out of “past” and “future,” and out of “this” and “that.”

As long as we conceive reality in terms of self and time, as a “me” who is someplace and can go some other place, then we are not realising that going forwards, going backwards, and standing still are all entirely dependent upon the relative truths “of self, locality, and time. In terms of physical reality, there is a coming and going. But there’s also that place of transcendence where there is no coming or going. Think about it. Where can we truly go? Do we ever really go anywhere? Wherever we go we are always “here,” right? To resolve the question, “Where can you go?” we have to let go—let go of self, let go of time, let go of place. In that abandonment of self, time, and place, all questions are resolved.

Ancient Teachings on Nonabiding

This principle of nonabiding is also contained within the ancient Theravāda teachings. It wasn’t just Ajahn Chah’s personal insight or the legacy of some stray Nyingmapa lama who wandered over the mountains and fetched up in northeast Thailand 100 years ago. Right in the Pali Canon, the Buddha points directly to this. In the Udāna (the collection of “Inspired Utterances” of the Buddha), he says:

There is that sphere of being where there is no earth, no water, no fire, nor wind; no experience of infinity of space, of infinity of consciousness, of no-thingness, or even of neither-perception-nor-non-perception; here there is neither this world nor another world, neither moon nor sun; this sphere of being I call neither a coming nor a going nor a staying still, neither a dying nor a reappearance; it has no basis, no evolution, and no support: it is the end of dukkha. (UD. 8.1)

Rigpa, nondual awareness, is the direct knowing of this. It’s the quality of mind that knows, while abiding nowhere.

There is also the Bahiya Sutta:

“In the seen, there is only the seen,

in the heard, there is only the heard,

in the sensed, there is only the sensed,

in the cognized, there is only the cognized.

Thus you should see that indeed there is no thing here;

this, Bāhiya, is how you should train yourself.

Since, Bāhiya, there is for you

in the seen, only the seen,

in the heard, only the heard,

in the sensed, only the sensed,

in the cognized, only the cognized,

and you see that there is no thing here,

you will therefore see that

indeed there is no thing there.

As you see that there is no thing there,

you will see that

you are therefore located neither in the world of this,

nor in the world of that,

nor in any place

betwixt the two.

This alone is the end of suffering.” (UD. 1.10)

“Where” Does Not Apply

What does it mean to say, “There is no thing there”? It is talking about the realm of the object; it implies that we recognise that “the seen is merely the seen.” That’s it. There are forms, shapes, colours, and so forth, but there is no thing there. There is no real substance, no solidity, and no self-existent reality. All there is, is the quality of experience itself. No more, no less. There is just seeing, hearing, feeling, sensing, cognizing. And the mind naming it all is also just another experience: “the space of the Dharma hall I’m in,” “Ajahn Amaro’s voice,” “here is the thought, ‘Am I understanding this?’ Now another thought, ‘Am I not understanding this?’”

There is what is seen, heard, tasted, and so on, but there is no thing-ness, no solid, independent entity that this experience “refers to.

As this insight matures, not only do we realize that there is no thing “out there,” but we also realize there is no solid thing “in here,” no independent and fixed entity that is the experiencer. This is talking about the realm of the subject.

The practice of nonabiding is a process of emptying out the objective and subjective domains, truly seeing that both the object and subject are intrinsically empty. If we can see that both the subjective and objective are empty, if there’s no real “in here” or “out there,” where could the feeling of I-ness and meness and my-ness locate itself? As the Buddha said to Bāhiya, “You will not be able to find your self either in the world of this [subject] or in the world of that [object] or anywhere between the two.

Continued next week, Jan/04/ 24

Source of Ajahn Amaro’s text: https://www.abhayagiri.org/media/books/amaro_small_boat_great_mountain.pdf

Image: USGS United States Geological Survey, The Lena River Delta Russia

You must be logged in to post a comment.