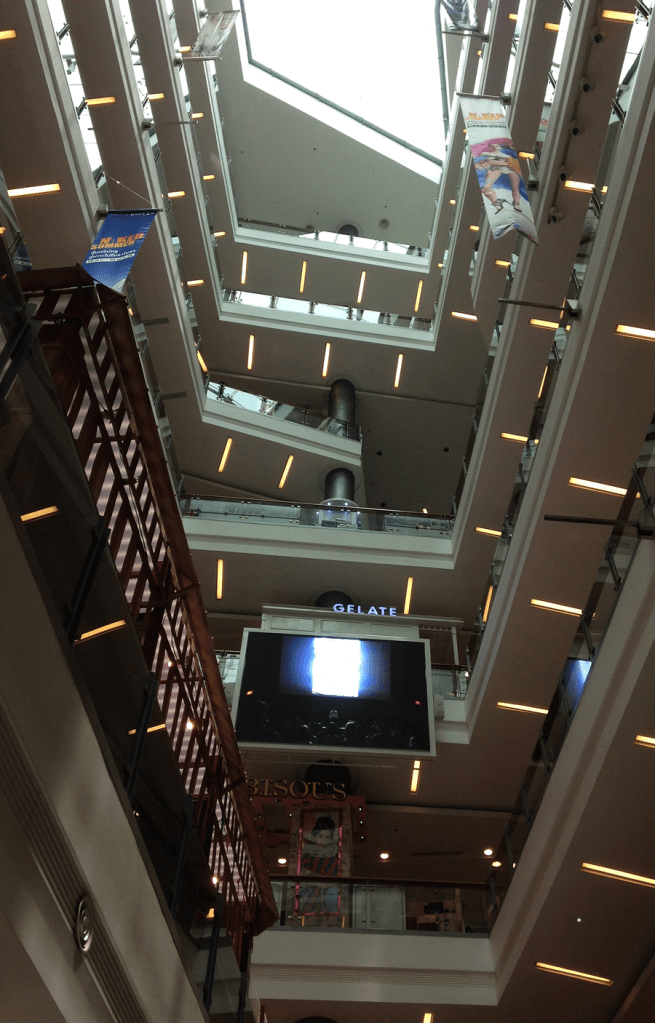

New Delhi: Mall architecture in Asia, concrete and steel shrines to maya (illusion) –they even named a shopping mall ‘MAYA’ in Chiang Mai. The population is presented with the idea; step into the illusion… a lightweight upbeat city culture, air-conditioned, bright and colourful. Something hopelessly inevitable about it all careering towards the Western consumer culture – except that in the East, people are more likely to be careful about the money in their purse. Cultural tradition, awareness and inherited spirituality; besides, everybody here knows that if somebody is in the market trying to sell you something, it means you have the option to negotiate a fair price… not so in the mall, and that’s why the population are unwilling to engage with it.

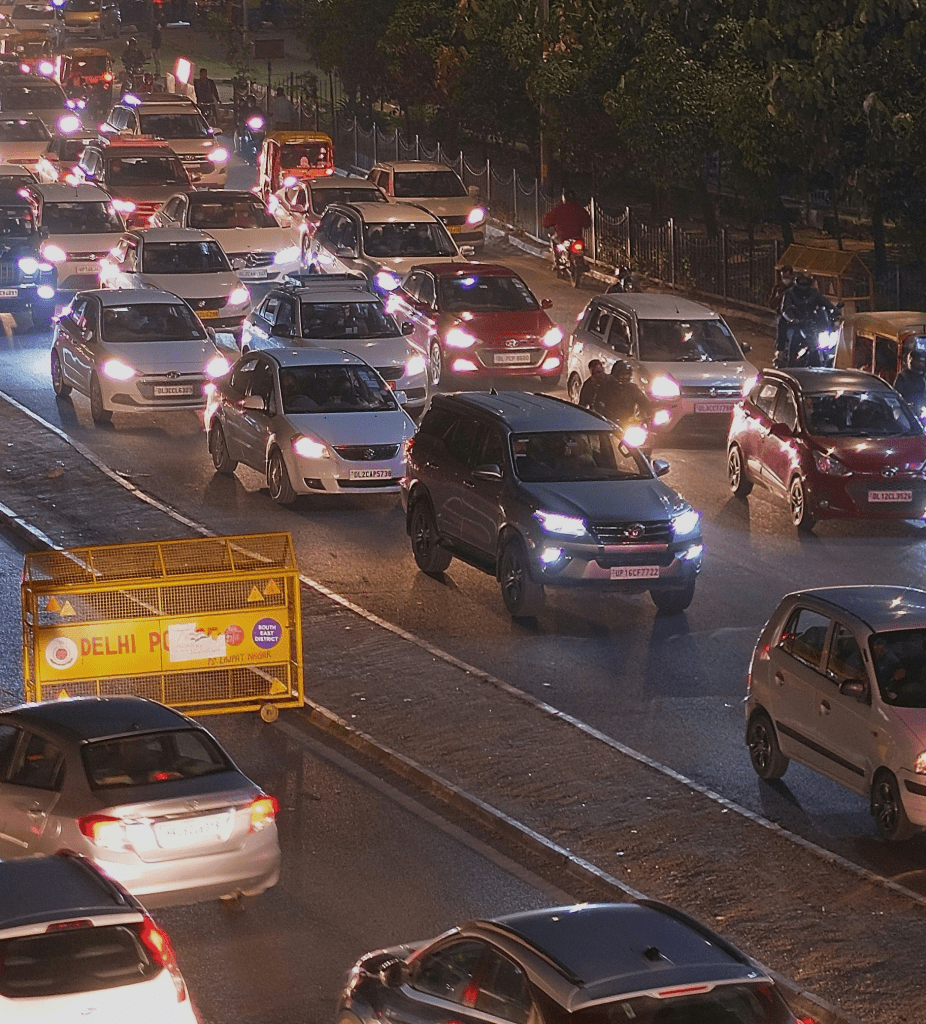

Here in India, the Mall culture affects only a small percentage of the population (sounds like a virus) and, I have to say I’m sometimes part of that minority; the need for essential things for devices, bookshops and a good baker. To get to our shopping mall we have to drive out of town and the three-building complex is situated in an undeveloped area – there’s a fourth building going up at the time of writing. Construction site workers’ community nearby, chickens and goats in a hot dry, dusty landscape. Come off the highway, through a great winding turn of rough unsurfaced road, potholes and puddles of water and into the short entry, manned by security – car examined, mirrors held underneath, look in the trunk, the engine. More security at the entrance, metal detector and security guards carry out a full body search before you get in the door.

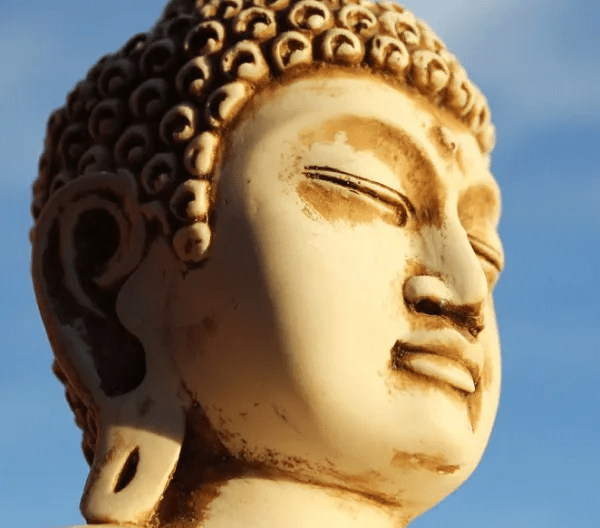

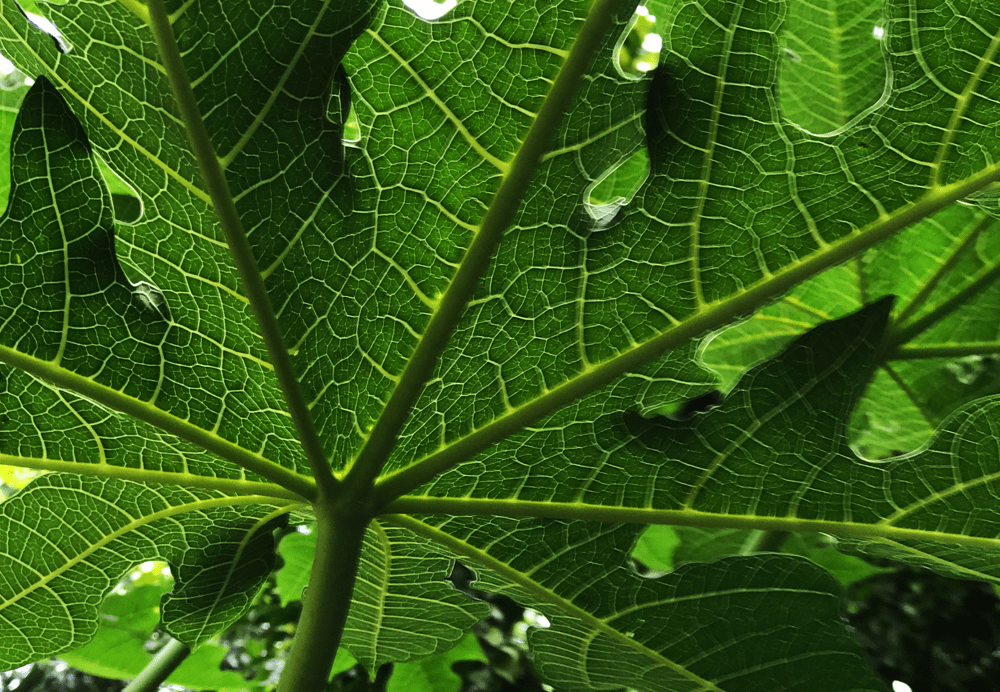

It’s as if the whole concept of consumerism is subject to scrutiny; not as easy as it is in the West to simply be pulled into the mall and disinclined to escape from the illusion. The fact is, for many people there’s no way out, situated at the end of the consumerist food chain, as they are, and trapped in that predicament. No alternative, we have to purchase the product because we can’t create it ourselves – so far away from doing things ourselves. People believe they can’t improvise… forgetting that the whole thing is improvised… language is improvised, life itself is improvised. All the systems that are in place were improvised to start with, and even though we may be subject to skilful marketing strategies, there’s still the innate ability to be creative, to improvise, to invent, to innovate, to find a way out of the illusion. The carnivorous marketing creatures have to be gently pushed into the background in order to bring what’s really meaningful in life into focus. First published September 5, 2015

‘The real is not something, it’s not anything. It’s not a phenomenon. You can’t think about it, you can’t create an image of it. So we say unconditioned, unborn, uncreated, unformed. Anatta (not-self), nirodha (cessation), nibbana (liberation). If you try to think about these words, you don’t get anywhere. Your mind stops; it’s like nothing. … if we’re expecting something from the meditation practice, some kind of Enlightenment, bright lights and world-trembling experiences, then we’re disappointed because expecting is another kind of desire, isn’t it?’ [The End of the World is Here, Ajahn Sumedho]

You must be logged in to post a comment.