Ajahn Sucitto

[Excerpts from “Kamma and the End of Kamma”]

‘Bhikkhus, for a virtuous person, one whose behavior is virtuous, no volition [cetanā] need be exerted: “Let non-regret arise in me.” It is natural that non-regret arises in a virtuous person, one whose behavior is virtuous.

‘For one without regret no volition need be exerted: “Let joy arise in me.” It is natural that joy arises in one without regret.

‘For one who is joyful no volition need be exerted: “Let rapture arise in me.” It is natural that rapture arises in one who is joyful.

‘For one with a rapturous mind no volition need be exerted: “Let my body be tranquil.” It is natural that the body of one with a rapturous mind is tranquil.

‘For one tranquil in body no volition need be exerted: “Let me feel pleasure.” It is natural that one tranquil in body feels pleasure.

‘For one feeling pleasure no volition need be exerted: “Let my mind be concentrated.” It is natural that the mind of one feeling pleasure is concentrated.

‘For one who is concentrated no volition need be exerted: “Let me know and see things as they really are.” It is natural that one who is concentrated knows and sees things as they really are.

‘For one who knows and sees things as they really are no volition need be exerted: “Let me be disenchanted and dispassionate.” It is natural that one who knows and sees things as they really are is disenchanted and dispassionate.

‘For one who is disenchanted and dispassionate no volition need be exerted: “Let me realize the knowledge and vision of “liberation.” It is natural that one who is disenchanted and dispassionate realizes the knowledge and vision of liberation.’

(A.10:2; B. Bodhi, trans.)

Another major distortion is the assumption that thinking will make our lives happy and solid – that pre-judgement sets up all kinds of stress. We might, for example, become an incessant thinker, or someone who delights in thinking and enjoys generating ideas. Of course, some ideas are interesting, and it’s great to link up a remembered fact with an imaginative proposal and start nudging them towards a conclusion. And yet this inner speech can be so absorbing that we don’t see or think beyond the range of what we already know or have an attitude around; so we get tunnel vision, become obsessive and lose that open awareness within which one’s ideas can be held in a broader perspective, other people’s angles and sensitivities listened to, and the energy of thinking can be peacefully relaxed. In fact, if the energies of conceiving and evaluating, planning and speculating can’t be moderated or discharged, the system burns out with nervous stress.[22]

However, thinking about how to stop thinking only adds more energy and conflict to the mix. This is why meditative training directs thinking. You skim off what’s unskilful or unnecessary to consider right now, then steer your thoughtfulness towards the grounded presence of the body, taking in how it feels.

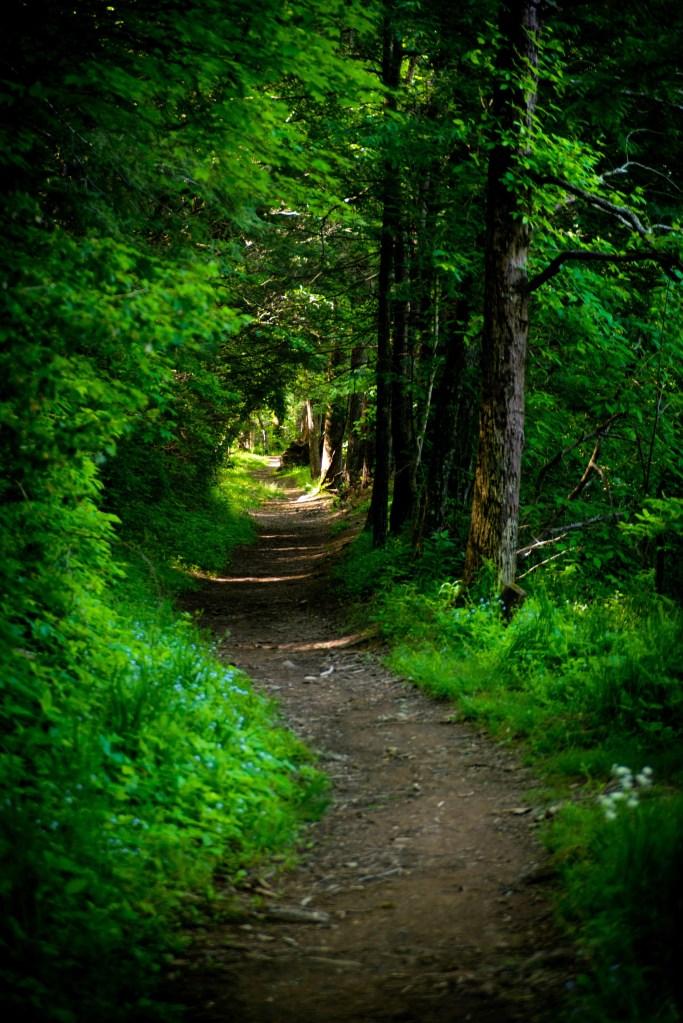

In this way, you steady the body, and through focusing on calm, repetitive experiences such as walking at a moderate pace, or breathing in a full and relaxed way from the abdomen, allow the citta to relax and open. Spreading attention slowly over the body as if in a slow massage is another good approach, one that adopts citta’s response to pleasure. You also can do this while standing, using the sense of balance to steady the mind. Take the time to notice the feeling of space around your body; then sit, walk or stand feeling that space, doing nothing more than being present with the embodied system. Deepen into simple moment-by-moment attitudes of well-wishing: ‘May I be well’ … ‘May others be well.’

I suggest this approach because attitude affects intention, which is the leader in the programming process. For many people, the energy of intention is set to the hyperactive mode of the business model: ‘You’ve got to work hard. Get out there and make it work for you.’ But if your heart is passionate or forceful, then your body gets signals to give you more energy, so your nervous system gets overstimulated and you tense up. Just notice how much nervous energy you can expend in getting emotionally worked up about things; notice how draining that can be. So, in meditation, train yourself to find a balance of resolve and receptivity rather than sustain ideals or imperatives that you can’t back up through the body’s energy or are beyond your psychological capacity. ‘Sitting here until I realize complete enlightenment’ is more likely to rupture your knee ligaments and stir up psychological turmoil than achieve the desired result.

A downshift in terms of speed and goals is a major shift. But you can begin by adjusting your attitude to one that makes the mind workable, fluid and curious. You move from ‘I’ve got to get it right’ to ‘How is this? Let’s take things a moment at a time.’ With this, you steady your energy, and use attitudes and intentions that bring your heart into play – so that it will be a supportive participant in this interconnected process.

This meditative kamma can then tone up the basis of all your intelligences; this brings around bodily ease, interrupts compulsive or habitual thinking, and also enables you to exercise authority over what you think about and how. And as this is about resetting your own conscious system, you can take the practice and its results with you wherever you go.

Continued next week 03 October 2024

You must be logged in to post a comment.