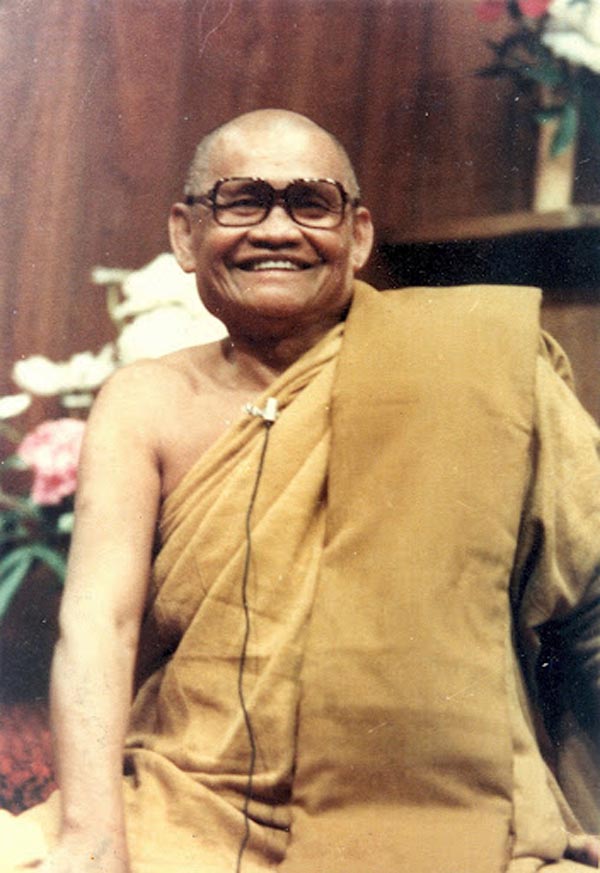

Ajahn Chah

[Excerpts from a longer Dhamma talk titled: The Path to Peace]

It is the mind which gives orders to the body. The body has to depend on the mind before it can function. However, the mind itself is constantly subject to different objects contacting and conditioning it before it can have any effect on the body. As you turn attention inwards and reflect on the Dhamma, the wisdom faculty gradually matures, and eventually, you are left contemplating the mind and mind-objects, which means that you start to experience the body, rūpadhamma, as arūpadhamma, formless. Through your insight, you’re no longer uncertain in your understanding of the body and the way it is. The mind experiences the body’s physical characteristics as arūpadhamma or formless objects, which come into contact with the mind. Ultimately, you’re contemplating just the mind and mind-objects—those objects which come into your consciousness. Now, examining the true nature of the mind, you can observe that in its natural state, it has no preoccupations or issues prevailing upon it. It’s like a piece of cloth or a flag that has been tied to the end of a pole—as long as it’s on its own and undisturbed, nothing will happen to it. A leaf on a tree is another example. Ordinarily, it remains quiet and unperturbed. If it moves or flutters, this must be due to the wind, an external force. Normally, nothing much happens to leaves—they remain still. They don’t go looking to get involved with anything or anybody. When they start to move, it must be due to the influence of something external, such as the wind, which makes them swing back and forth. It’s a natural state. The mind is the same. In it, there exists no loving or hating, nor does it seek to blame other people. It is independent, existing in a state of purity that is truly clear, radiant and untarnished. In its pure state, the mind is peaceful, without happiness or suffering—indeed, not experiencing any feeling at all. This is the true state of the mind. The purpose of practice, then, is to seek inwardly, searching and investigating until you reach the original mind; also known as the Pure Mind, the mind without attachment.”

The Pure Mind doesn’t get affected by mind-objects. In other words, it doesn’t chase after the different kinds of pleasant and unpleasant mind-objects. Rather, the mind is in a state of continuous knowing and wakefulness, thoroughly mindful of all its experiencing. When the mind is like this, no pleasant or unpleasant mind-objects it experiences will be able to disturb it. The mind doesn’t become anything. In other words, nothing can shake it. Why? Because there is awareness. The mind knows itself as pure. It has evolved its own true independence, has reached its original state. How is it able to bring this original state into existence? Through the faculty of mindfulness wisely reflecting and seeing that all things are merely conditions arising out of the influence of elements, without any individual being controlling them.”

“This is how it is with the happiness and suffering we experience. When these mental states arise, they’re just happiness and suffering. There’s no owner of the happiness. The mind is not the owner of the suffering—mental states do not belong to the mind. Look at it for yourself. In reality, these are not affairs of the mind, they’re separate and distinct. Happiness is just the state of happiness; suffering is just the state of suffering.”

You are merely the knower of these things. In the past, because the roots of greed, hatred, and delusion already existed in the mind, whenever you caught sight of the slightest pleasant or unpleasant mind-object, the mind would react immediately—you would take hold of it and have to experience either happiness or suffering. You would be continuously indulging in states of happiness and suffering. That’s the way it is as long as the mind doesn’t know itself—as long as it’s not bright and illuminated. The mind is not free. It is influenced by whatever mind-objects it experiences. In other words, it is without a refuge, unable to truly depend on itself. You receive a pleasant mental impression and get into a good mood. The mind forgets itself. In contrast, the original mind is beyond good and bad. This is the original nature of the mind. If you feel happy over experiencing a pleasant mind-object, that is delusion. If you feel unhappy over experiencing an unpleasant mind-object, that is delusion. Unpleasant mind-objects make you suffer and pleasant ones make you happy—this is the world. Mind-objects come with the world. They are the world. They give rise to happiness and suffering, good and evil, and everything that is subject to impermanence and uncertainty.

As you reflect like this, penetrating deeper and deeper inwards, the mind becomes progressively more refined, going beyond the coarser defilements. The more firmly the mind is concentrated, the more resolute in the practice it becomes. The more you contemplate, the more confident you become. The mind becomes truly stable – to the point where it can’t be swayed by anything at all. You are absolutely confident that no single mind-object has the power to shake it. Mind-objects are mind-objects; the mind is the mind. The mind experiences good and bad mental states, happiness and suffering, because it is deluded by mind-objects. If it isn’t deluded by mind-objects, there’s no suffering. The undeluded mind can’t be shaken. This phenomenon is a state of awareness, where all things and phenomena are viewed entirely as dhātu (natural elements) arising and passing away – just that much. It might be possible to have this experience and yet still be unable to fully let go. Whether you can or can’t let go, don’t let this bother you. Before anything else, you must at least develop and sustain this level of awareness or fixed determination in the mind. You have to keep applying the pressure and destroying defilements through determined effort, penetrating deeper and deeper into the practice.

Having discerned the Dhamma in this way, the mind will withdraw to a less intense level of practice, which the Buddha and subsequent Buddhist scriptures describe as the Gotrabhū citta. The Gotrabhū citta refers to the mind which has experienced going beyond the boundaries of the ordinary human mind. It is the mind of the puthujjana (ordinary unenlightened individual) breaking through into the realm of the ariyan (Noble One) – however, this phenomenon still takes place within the mind of the ordinary unenlightened individual like ourselves. The Gotrabhū puggala is someone, who, having progressed in their practice until they gain temporary experience of Nibbāna (enlightenment), withdraws from it and continues practising on another level, because they have not yet completely cut off all defilements. It’s like someone who is in the middle of stepping across a stream, with one foot on the near bank, and the other on the far side. They know for sure that there are two sides to the stream, but are unable to cross over it completely and so step back. The understanding that there exist two sides to the stream is similar to that of the Gotrabhū puggala or the Gotrabhū citta. It means that you know the way to go beyond the defilements, but are still unable to go there, and so step back. Once you know for yourself that this state truly exists, this knowledge remains with you constantly as you continue to practise meditation and develop your pāramī. You are both certain of the goal and the most direct way to reach it.

Editor’s note: I found a section of this talk in the website “Path and Press: an existential approach to the Buddha’s Teaching.” From here I found a reference to the original source: “The Path to Peace. Here are the links”

https://pathpress.wordpress.com/2019/08/25/ajahn-chah-and-the-original-mind/

You must be logged in to post a comment.