Leigh Brassington

Editorial note: I was surprised to discover there are so many words in the Pali language that mean Joy or are related in some way: Somanassā, Pīti, Sukha, Mudita, Sumanā, Nandi, Ananda, and there are others. If you want to know more about Joy, you need to check out the video “Joy as Path” by Ajahn Kovilo in the context of Transcendental Dependent Origination (Before you view the video, please return the counter to zero. My mistake, apologies)

Now we turn to Leigh Brassington’s text, a follow-up on last week’s post, “Moment-to-Moment Consciousness.”

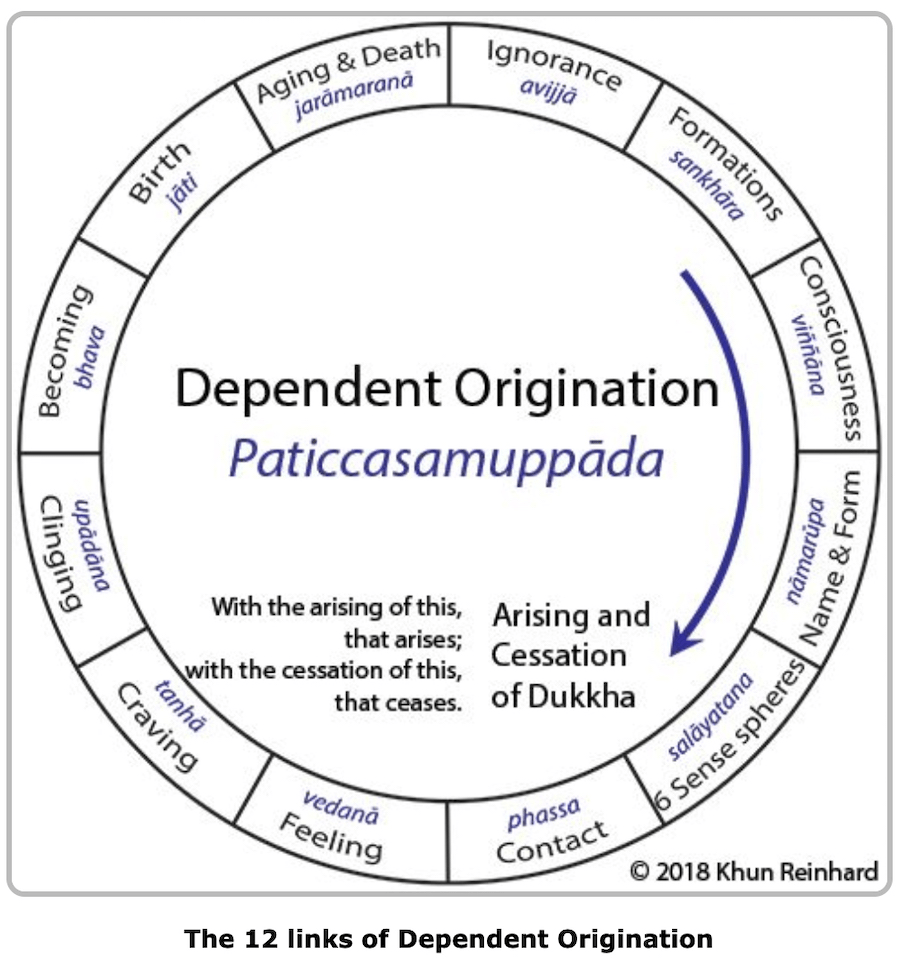

The sutta on Transcendental Dependent Origination is one of the more interesting ways that dependent origination is used to teach more than just the moment-to-moment activity we experience with our sense-contacts.

“And what is the result of dukkha? Here, someone overcome by dukkha, with a mind obsessed by it, sorrows, languishes, and laments; they weep beating their breast and become confused. Or else, overcome by dukkha, with a mind obsessed by it, they embark upon a search outside, saying: ‘Who knows one or two words for putting an end to this dukkha?’ Dukkha, I say, results either in confusion or in a search. This is called the result of dukkha.” AN 6.63

Once we acknowledge the seeming all-pervasiveness of dukkha, we begin searching for a solution to this problem. When we find a promising path, we try it out and if it seems like it just might work, we gain confidence in that path [Upanisa sutta, Samyutta 12.23.1]. The sequence is, Dukkha (Suffering) is a necessary condition for the arising of Saddha. Saddha is often translated as “faith” but I think a better translation is “confidence.” This confidence is not self-confidence, rather it’s confidence in a proposed method for overcoming Dukkha.

From Saddha as a necessary condition, Pāmojja arises. Pāmojja is usually translated as “worldly joy.” This joy arises because the path that one now has confidence in is starting to work. In particular, the Buddha frequently teaches that Pāmojja arises during meditation when one overcomes the five hindrances: sensual desire, ill will & hatred, sloth & torpor, restless & remorse, and doubt. [See below for an analysis of the five hindrances]

Having generated this Worldly Joy, one can now generate Pīti. Pīti gets variously translated as “rapture” or “euphoria” or “ecstasy” or “delight.” My favorite translation is “glee.” Pīti is primarily a physical sensation that sweeps you powerfully into an altered state. But Pīti is not solely physical; as the suttas say, “on account of the presence of Pīti there is mental exhilaration.”

When the Pīti calms down, Passaddhi – tranquility – arises. Then because of that tranquility, Sukha – joy, happiness – arises. Upon letting go of the pleasure of the Sukha, Samādhi – deep concentration – manifests. These five – Pāmojja, Pīti, Passaddhi, Sukha, and Samādhi – are the mind’s movement into and through the four jhānas, the purpose of which is to generate the deep concentration “that turbo-charges one’s insight practice. Arising dependent on a mind that is “thus concentrated, pure and bright, unblemished, free from defects, malleable, wieldy, steady and attained to imperturbability” is Yathābhūtañāṇadassana – knowing and seeing things as they are. These are the insights into the nature of reality that begin the process of freeing one from dukkha. [First, let’s look at the five hindrances.]

The five hindrances (nīvaraṇa)

Whether we find ourselves in a storm of emotions or sleepy, anxious, bored, or daydreaming, meditation shines a light on all the ways the heart and mind can be uncomfortable and resist settling down. These difficult energies we encounter in both meditation and ordinary life are known as the five hindrances (nīvaraṇa), and engaging with them skillfully can change our practice time from a frustrating chore to the nourishing and insightful experience we know is possible.

The concentrated mind is focused and relaxed, and the cultivation of samādhi depends more on being able to let go into calm, easeful presence than focusing the attention relentlessly on one thing. The hindrances obstruct concentration because they all are active in a way that’s not helpful for calm and clarity.

The hindrances can be thought of as symptoms of an underlying disconnection or dissatisfaction (dukkha). They are habits of the heart and mind that, like many of our unconscious tendencies, are rooted in the heart’s attempt to stay safe in an unsafe world. They are reactive, judgmental, and above all, not under our conscious control.

The instructions for bringing mindfulness to the hindrances start with recognizing when a hindrance is present and when it is not. These are habitual energies, and can be so familiar that they feel like part of our personality, but in our practice, we begin to see that they are sometimes present and sometimes not, depending on the conditions we find ourselves in. We are then encouraged to actively set up the conditions for the hindrances to diminish. [Click on the link below to the original Spirit Rock Practice Guide for detailed analyses on the five hindrances]

https://www.spiritrock.org/practice-guides/the-five-hindrances

Transcendental dependent origination continued:

The Remaining Steps

When the insights are deep enough, when one knows and sees what’s actually happening, this can lead to Nibbidā. The best translation of nibbidā is “disenchantment.” We are currently under the spell that we will find relief from dukkha via the things of this world. But when we can see deeply enough the way things really are, we become dis-enchanted; the spell is broken.

Being disenchanted, we can become Virāga. The usual translation of Virāga is “dispassion;” but this dispassion doesn’t mean a flat affect. It means one’s mind is not colored by the things of the world that one has become disenchanted with and which have been seen to no longer be an exit from Dukkha.

Dependent on dispassion, Vimutti arises – release/deliverance/emancipation. Finally with emancipation, Āsavakkhaye ñāṇa is gained – the knowledge of the destruction of the āsavas. The āsavas are the intoxicants – we are intoxicated with sense pleasures, we are intoxicated with becoming, and we are intoxicated by ignorance. The overcoming of these intoxicants is the goal of practice; and with emancipation, one knows one has done what needed to be done, one has become an arahant.

Now we can build the following chart of Transcendental Dependent Origination – in the reverse order:

Knowledge of destruction of the āsavas (āsavakkhaye ñāṇa) arises dependent upon

Emancipation (vimutti) arises dependent upon

Dispassion (virāga) arises dependent upon

Disenchantment (nibbida) arises dependent upon

Knowledge and vision of things as they are (yathābhūtañāṇadassana) arises dependent upon

Concentration (samādhi) arises dependent upon

Happiness (sukha) arises dependent upon

Tranquility (passaddhi) arises dependent upon

Rapture (pīti) arises dependent upon

Worldly Joy (pāmojja) arises dependent upon

Confidence (saddha) arises dependent upon

Dukkha arises dependent upon the other eleven mundane links.

This text is a composite of excerpts from “Dependent Origination and Emptiness” by Leigh Brassington, whicjh is a free Dhamma publication. Click on the link to see how to download:

You must be logged in to post a comment.