Ajahn Sucitto

The Blessing of Skilful Attention

Whoever cultivates goodness is made glad,

right now and in the future – such a one is

gladdened in both instances.

The purity of one’s deeds, if carefully recollected,

is a cause for gladness and joy.

Dhammapada: ‘The Pairs’, 16

In the last few weeks, a Buddha-image has been created in this monastery by Ajahn Nonti. He’s a renowned sculptor in Thailand, and he came to Cittaviveka to fashion this image as an act of generosity. It’s been a lovely occasion because the Buddha-image is being made in a friendly and enjoyable way. Many people have been able to join in and help with it. Yesterday there were nine people at work sanding the Buddha-image. It’s not that big, yet nine people were scrubbing away on it, and enjoying doing that together.

Bright and Dark Kamma Arise from the Heart

Nine people working together in a friendly way is a good thing to have happening. Moreover, the work was all voluntary, and came about with no prior arrangement: people got interested in the project and gathered around it. It’s because of what the Buddha represents, and because people love to participate in good causes. That’s the magic of bright kamma. It arises around doing something which will have long-term significance, and also from acting in a way that feels ‘bright’ rather than intense or compulsive. Kamma – intentional or volitional action – always has a result or residue, and here it’s obvious that the bright kamma is having good results. There’s an immediate result – people are feeling happy through working together. And there’s a long-term result – they are doing something that will bring benefit to others.

In a few days we hope to install the Buddha-image in the meditation hall. It’s an image that makes me feel good when I look at it. It has a soft, inviting quality that brings up a sense of feeling welcome and relaxed. This is a very good reminder for meditation. Sometimes people can get tense about ‘enlightenment’, and that brings up worries, pressure, and all kinds of views; but often what we really need is to feel welcomed and blessed. This is quite a turnaround from our normal mind-set; but when we are sitting somewhere where we feel trusted, where there’s benevolence around us, we can let ourselves open up. And as we open our hearts, we can sense a clarity of presence, and firm up around that. This firmness arising from gentleness is what the Buddha-image stands for. It reminds us that there was an historical Buddha whose awakening is still glowing through the ages – but when this is also presented as a heart-impression in the here and now, rather than as a piece of history, it carries more resonance. Then the image serves as a direct impression of what bright kamma feels like.

‘Bright’ kamma is the term used in the scriptures to denote good action, or that which leads to positive results. This is not a theory or a legal judgement; if you linger in the heart behind skilful actions, you can feel a bright, uplifting tone. Bright kamma is steady and imparts clarity; it has an energy that’s conducive to meditation. Dark kamma, on the other hand, lacks clarity and feels corrosive. As it makes the heart feel so unpleasant, mostly attention doesn’t want to go there; the heart gets jittery and distracts instead. So, this is something to check inwardly: can we rest and comfortably bear witness to the heart behind our actions? Do our thoughts and impulses come from a bright or dark state? Even in the case of owning up to some painful truth about our actions, isn’t there a brightness, a certain dignity, when we do that willingly? Look for brightness in occasions when your heart comes forth rather than in times of superficial ease or of being dutifully good. That bright, steady tone rather “than casualness or pressurized obedience, indicates the best basis for action.

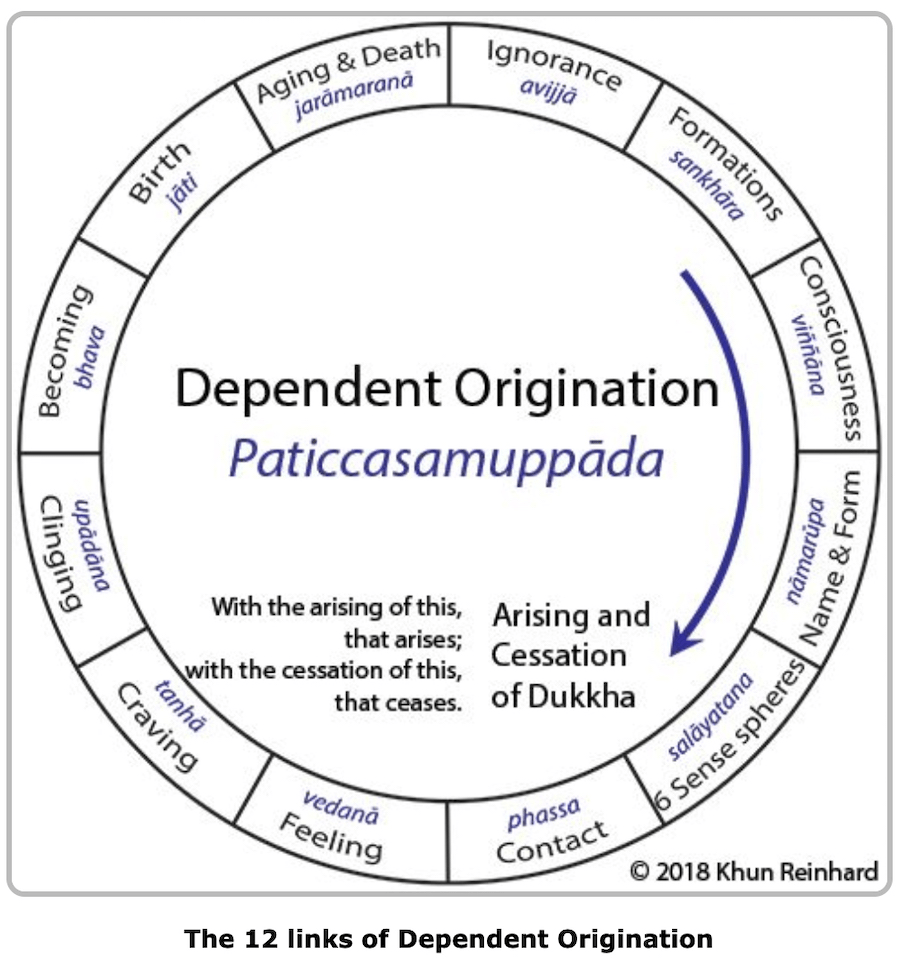

Sense and Meaning: The Perceptual Process

The energy of kamma originates in the heart, citta. It can move out through body (kāya) and speech (vāca – which includes the ‘internal speech’ of thinking) and mind (manas). Both manas and citta can be translated as ‘mind’, but the terms refer to different mental functions. ‘Manas’ refers to the mental organ that focuses on the input of any of the senses. This action is called ‘attention’ (manasikāra). So manas defines and articulates; it scans the other senses and translates them into perceptions and concepts (saññā). Tonally, it’s quite neutral. It’s not happy or sad; in itself, it just defines, ‘That’s that.’

Citta, on the other hand, is the awareness that receives the impressions that attention has brought to it, is affected and responds. It adds pleasure and pain to the perceptions that manas delivers, and these effects generate mind-states of varying degrees of happiness and unhappiness. Owing to this emotional aspect, I refer to citta as ‘heart’. Note that citta doesn’t access the senses directly. Instead, it adds feeling to the perceptions that attention has brought it; but with that, the initial moment of perception gets intensified to give a ‘felt sense’. This is a simple note such as ‘smooth’, ‘glowing’, ‘foggy’, ‘intense’. Then as attention rapidly gathers around that sense, a felt meaning crystallizes. For example, manas may decide that an orange-coloured globe of a certain size is probably an orange. From that meaning, further felt senses such as ‘tasty, healthy’ may arise and resonate in the heart. So, a mind-state based on desire arises. And even though all this originates in mere interpretations, intention springs up – and citta moves attention, intention and body towards the orange with an interest in eating it.

In this way, impulse/intention occurs as a response to a felt meaning that itself has been conjured up by a graduated and felt perceptual process. This is how mental kamma arises. And the result of citta being affected in this way is that the meaning is established as a reference point. Then the next time I see or think of an orange, that established perception that ‘Oranges are tasty; they’re good for me’ becomes the starting point for action. But is that interpretation always correct? Ever bitten into a rotten orange, or been fooled by a plastic replica? More significantly, don’t perceptions of people need a good amount of adjustment over time? How true is perception?

Perception is initiated when attention turns towards a particular sense-object. So, all contact depends on attention. Take the case of when you’re intensely focused on reading a book or watching a movie: awareness of your body, of the pressure of the chair, and maybe even a minor ache or pain, disappears. The mind’s attention is absorbed in seeing and processing the seen, so other impressions don’t get registered. Contact with the chair has disappeared because one’s attention was elsewhere. How real then is contact?

Contact is actually of two kinds. The contact that occurs when the mind registers something touching the senses is called ‘disturbance-contact’ (paṭigha-phassa). But when manas ‘touches’ the citta at a sensitive point, ‘designation-contact’ (adhivacana-phassa) is evoked – along with a felt sense. Disturbance-contact occurs in the mind-organ, and designation-contact occurs in the heart; and it is designation-contact, the heart’s impression, rather than contact with something external, that both moves us and stays with us as a meaning. For example, ‘dog’ is tonally a neutral perception that we would agree upon as a definition of a certain kind of animal. But in terms of citta, that ‘dog’ could mean ‘savage creature that can bite or has bitten me’ or ‘loyal, cuddly friend that will protect me.’ Such contact is therefore formed by previous action, but present-day impulses and actions are based on it. Thus, the old perception shapes me; in this case, as a fearful or confident person. And I act from that basis. This is why it is said: ‘Contact is the cause of kamma.’

Continued next week 15 August 2024

Link to the original text. Download a few pages, or the whole book free of charge. It’s a Dhamma publication:

https://www.abhayagiri.org/books/458-kamma-and-the-end-of-kamma

You must be logged in to post a comment.