Continued excerpts from, “Kamma and the end of Kamma,” by Ajahn Sucitto

Samādhi is generated through skilful intentions in the present. It also relies upon already having a mind-set that settles easily, and it naturally sets up programs for the future: one inclines to simpler, and more peaceful ways of living. Samādhi provides us with a temporary liberation from some kammic themes – such as sense-desire, ill-will, worry, or despond – and it gives us a firm, grounded mind which feels bright. But samādhi itself is still bound up in time and cause and effect; it is kamma, bright and refined, but still formulated.

Also, it takes time to develop samādhi. And meanwhile, the very notion of ‘getting samādhi’ can trigger stressful formulations such as: ‘Got to get there’, ‘Can’t do it’ and so on. Accordingly, the learning point for both one who does, and for one who doesn’t, develop much samādhi, is to handle and review the programming. ‘How much craving is in this? How much “me holding on” is there?’ That’s the process of insight. It’s always relevant.

The results of holding on can be discerned in our most obvious and continual form of kamma: thinking. Thinking plays a big part in our lives, governing how we relate to circumstances and other people, determining what potentials we want to bring forth and where interesting opportunities might lie – and just reflecting, musing and daydreaming. So moderating and contemplating thought is an all-day practice. This practice offers understanding – and therefore a means of purifying one’s kamma, and even getting beyond it.

To do this, notice the tone or speed or raggedness that thinking has. By doing this, there is a disengagement from the topic or purpose of thinking; and your mind settles and connects to how the thought feels in the heart. When your heart is grounded in the body, you don’t get captured by the drive or emotional underpinning of thinking. Whether you have a great idea, or are eager to get your idea acted upon, or you don’t have a clue and feel ashamed of that – all that can be sensed and allowed to change into something more balanced. So this hinges on referring to the interconnected system of body, thought and heart. Ideally we want to direct our lives with the full set, so that we’re not just acting on whims and reactions, and our thoughts and ideas are supported by good and steady heart. That heart is where kamma arises, so you want to make sure it’s in good shape and is on board with what you’re proposing. Get it grounded in the body before you let the tide of thought rush in.

Once you settle the heart, you can evaluate the current of thought in terms of its effect. Sometimes it feels really pleasant in itself (like when people agree with me), but when I refer to how it sits in my heart and body, thinking can seem overdramatic, self-important, petty or unbalanced. Too often thinking closes the opportunity for the miraculous to occur, or for a fresh point of view to arise. And as the after-effect of all kamma is that a self-image gets created, do my thoughts make me into a fault-finder; a compulsive do-er; a habitual procrastinator; a feverish complicator; or a slightly grandiose attention-seeker? Does thinking keep my heart very busy being ‘me’, or could it be just a balanced response to what a situation needs – something that can dissolve without trace?

And as self-images do arise, can they be evaluated and witnessed with steady awareness? Can openness and goodwill arise in that awareness to know: ‘this is an image, this is old kamma, don’t act on this but let it pass?’ In this way, we can avoid making assumptions, established attitudes, and directed intentions into fixed identities. These are the blades of the spinning fan – stored up as citta-saṇkhārā. If you train in samādhi and paññā, those self-programs can be un-plugged. True actions don’t need an actor.

What underpins the automatic plugging-in is ignorance, the programming that is most fundamental to our suffering and stress. Ignorance is easy: pre-fabricated attitudes cut out the awkward process of being with things afresh. Ignorance gets seeded in the familiar and blossoms into the compulsive – which feels really solid and ‘me’. That’s how it is. But as the sense of self centres around people’s most compulsive behaviour, the personal self is so often experienced as the victim of habit, a being who’s locked into patterns and programs.

This is why it’s always remedial to attend to the kinds of kamma that are about not doing. The not-doing of harm, for example, is an absolutely vital intention to carry out – if enough of us followed this, it would change the world. And what about the other precepts? We can fulfil these, day after day and not notice it because our hearts and minds were elsewhere, believing we should do more and not noticing the not-doing mind. But the crucial Dhamma actions are just this: to disengage from the compulsive, and mindfully engage with the steady openness of your own interconnected intelligence.

For example, when a verbal exchange is getting overheated, you can attune to what’s happening in the body – the palms of the hands, the temples and the eyes are accessible indicators of energy. Does this energy need to be more carefully held? Sometimes I find that just acknowledging and adjusting the speed of speaking or walking shifts attitudes and moods; softening the gaze is also helpful. Say you’re feeling dull or depressed: is your body fully present …? Giving some attention there with a kindly attitude helps the energy to brighten up, and shifts the mind-state.

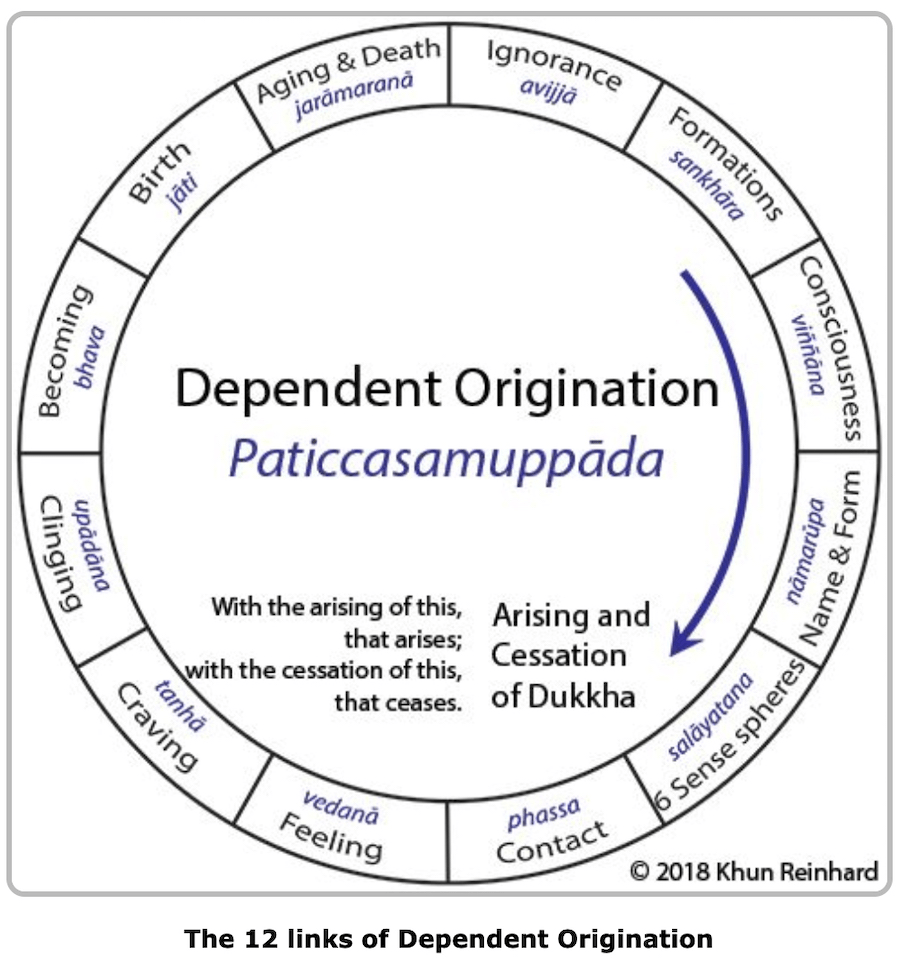

Holding on, gaining, succeeding, losing: the programs that saṇkhārā concoct – deliberate or instinctive, driving or drifting – can be witnessed. We can notice the surge of glee or despond, the lure of achievement, and the itch to get more. But we can focus on these impressions, heart-patterns and programs just as they are, rather than believing ‘this is me’; ‘this is mine’; ‘I take my stand on this’; or even ‘I am different from all this stuff.’ This is the focus of insight. It’s about witnessing programs: how they depend on self-views, how they arise based on feeling, attract a grasping, lead to the creation of ideas and notions, create a self – and so keep saṃsāra rolling on. With insight, you contemplate the rigmarole of success and failure, of what I am and what I will be: it’s all more kamma, more self-view, more stuff to get busy with. But if you see the endlessness of all that, you work with the self-patterning and cut off stressful programs. And that’s the only way to get free of kamma.

When that point becomes clear, deepening liberation depends on staying attentive and learning from what arises and passes through your awareness. Because when one relates to bodily, conceptual and emotional energies as programs, that doesn’t support the view ‘I am’. Being unsupported by that view, the basis of feeling is exposed; with disengagement and dispassion, that feeling doesn’t catch hold. But it’s like scratching an itch, or smoking a cigarette: even though you get the idea that it might be good to stop, your system won’t do it unless it gets an agreeable feel for the benefits of stopping, and you develop the resolve and skills to do so.

To this end, ethics place discernment where it most often needs to dwell; meditation blends body, thought and heart together into firmness, clarity and ease; and wise insight disbands the defective programs. Then we can handle life without getting thrown up and down by it. We don’t have to keep on proving ourselves, defending ourselves, creating ourselves as obligated, hopeless, misunderstood and so on. Kamma, and a heap of suffering, can cease.

Continued next week October 17, 2024

You must be logged in to post a comment.