Leigh Brasington

Editorial Note: Some of you may have noticed that last week I placed the name Leigh Brassington as the author of Christina Feldman’s piece on Dependent Origination. Sorry about that, in fact, I corrected it a day later. Increasing difficulty with my vision (AMD macular degeneration in the right eye) has made it impossible to write my own material,

https://dhammafootsteps.com/2012/10/04/neverending/

(click on the link to read an early post that refers to Dependent Origination). For the time being I’m focused on republishing sections from Dhamma publications which I find particularly worthwhile. So, what follows is Leigh Brassington’s clearly stated piece on Dependent Origination [Image: close-up of a sunflower seed by Mathew Schwartz, unsplash]

Here’s an example of what’s meant by moment-to-moment Dependent Origination: let’s say you’ve never had a mango. You’ve heard about mangos, and one day you go to the grocery store, and in the produce section there’s a sign that says “Mangos.” You’re like “Oh, I’ve heard about mangos, they’re supposed to be good.” There’s this funny looking fruit and you think, “I’ll buy a mango.” So, you buy a mango and you take it home. You figure out you’ve got to peel it; and of course, you make a big mess because that’s what happens the first time you attack a mango. Then you cut off a piece, and now you’ve got a piece of mango in your sticky fingers. You are conscious, you’ve got a mind and body, you’ve got working senses. The mango hits the tongue – contact, vedanā, pleasant vedanā, craving; “I’ll have another bite” and another bite. “This is good; I’m going to get me some more mangos. In fact, my friends Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice, they’ve never had a mango. I’m going to turn them on to mangos.” You have just given birth to the mango bringer. You go see your friends and you turn them on to mangos and they’re like “Great, this is wonderful, thank you!” And the next time you go see your friends you bring a mango, and they’re like “Great, thank you for the mango.” And the next time you bring a mango, they’re like “Oh, another mango.” And the next time you bring a mango, they’re like “What’s with all the mangos?” Oh, dear! death of the mango bringer.

What’s happening is that based on your sensory input and your cravings and clingings, you’re creating a sense of self. It’s not your physical birth that’s happening with every sense-contact; it’s the birth of the self. When you crave, there’s a sense of the craver. When you cling, there’s an even stronger sense of the clinger – me, I own it, mine. At first, at the craving stage, it’s “I want it”. At the clinging stage, it’s “I’ve got it and I’m going to keep it.” And this results in “bhava,” which I’ve been translating as “becoming,” and which could also mean “being and having.” Now you have this thing you’re craving. You have become the one who owns it, and you just gave birth to yourself as this owner. But because your sense of self is rather fragile – notice how we’re always seeking self-validation – it keeps dying on you and you’ve got to think it or emote it up again.

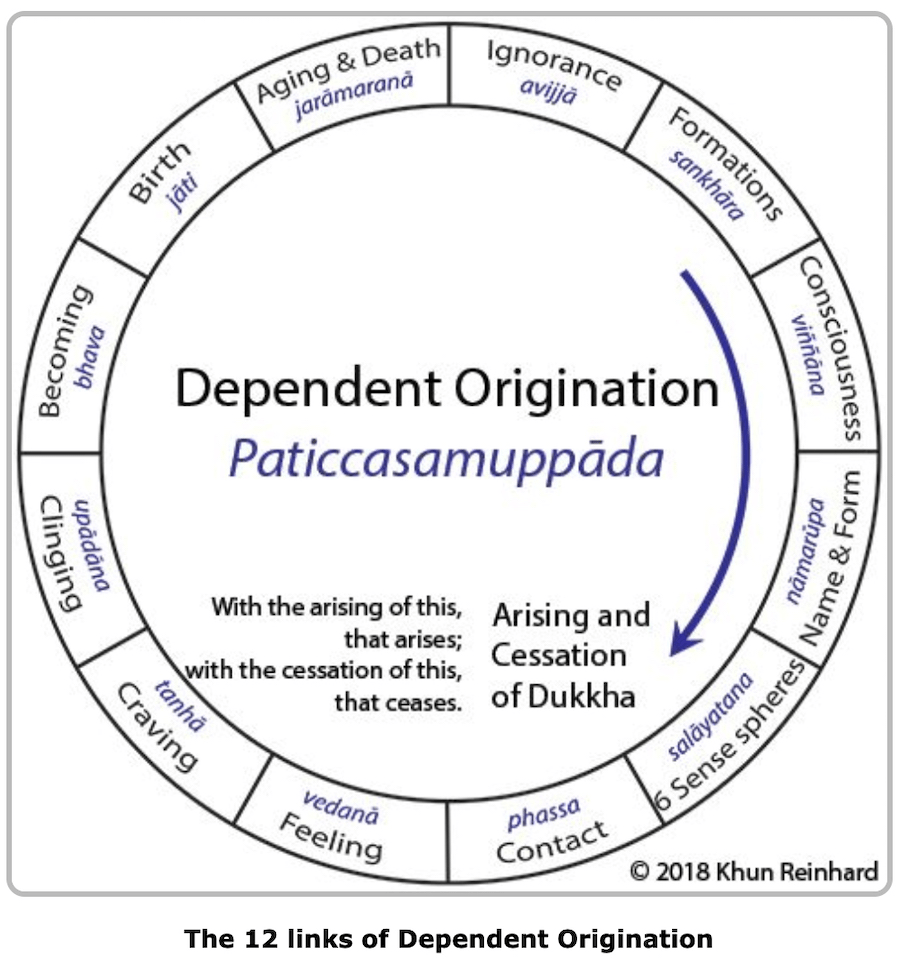

Examining the twelve links of dependent origination from a moment-to-moment perspective is probably the deepest and most important way to look at them. This spinning of the wheel of dependent origination leads to old age, sickness, death, pain, sorrow, grief, lamentation, and all the rest of the dukkha. The Buddha’s teaching is about the end of dukkha, and there are two ways to work on this. One is when there’s a sense-contact, and it produces vedanā – Stop! don’t go any further. Don’t go into the craving. There’s not much you can do before that. You’re conscious, you have a mind and body, your senses are engaged with the environment. You’re inevitably going to get contacts, and the contacts are going to produce the vedanā which are not under your control. The vedanā are happening in the old brain, the so-called reptilian structure, and that’s not under your control. It’s only after the vedanā that you have some opportunity to control what happens next.

Thankfully, the craving isn’t inevitable. Some of these links are inevitable. In other words, if you get born, it’s inevitable you’re going to die. But if you get a pleasant vedanā, it’s not inevitable that you’re going to fall into craving. What comes after vedanā is perception – the naming or conceptualizing of that sense-contact – and that’s not even mentioned in the twelve links of dependent origination. After perception, mental activity arises – saṅkhāra again, the thinking and emoting about the sense-contact that produced this vedanā. Some of the thinking and emoting is no problem. It’s only when it gets into the “I gotta have it, I gotta keep it” that the craving and clinging set in. Or “I gotta get rid of it, I gotta keep it away.” That’s where it gets to be a problem.

This is why the Second Foundation of Mindfulness is to pay attention to your vedanā. This is so that when you experience a pleasant vedanā, you know it, and you’re right there in that gap after the vedanā and before the onset of craving – and you can actually deal with the experience wisely. You can enjoy the pleasant vedanā, and just leave it at enjoying the pleasant vedanā. You can experience the unpleasant vedanā, and act, if necessary, based on the unpleasant vedanā without falling into craving and clinging. This is the strategy on a sense-contact by sense-contact basis. It’s a lot of work because we get a lot of sense-contacts. However, you need to be in there every time checking because the craving is liable to come up; and when it comes up, it’s a setup for dukkha. We don’t really seem to be able to pull this off all the time. Sometimes, yes, good, diminish your dukkha, you experience the sense-contact with its vedanā, enjoy it, let it go. But sometimes, you get lost and fall into craving and clinging.

But a long-term strategy is to go back to the very beginning of the list of the twelve links, and uproot the ignorance. Because without the ignorance, there are not the saṅkhāras, and without the saṅkhāras there’s no consciousness, mind-and-body, etc. That sounds a bit like annihilation, but really what it’s saying is that without the ignorance this whole tendency to wind up in craving and clinging just isn’t there. The key thing is to uproot that sense of self that is the craver and the clinger, to gain the unshakable deep understanding, based on experience, that this feeling of self is simply an illusion. You want to penetrate that illusion to such an extent that you don’t conceive of a self. Similarly, when you go to the beach and look out and see a ship sail over the horizon, you know it didn’t fall off the edge of the world. That sensory input does not lead to conceiving any “the edge of the world” as part of the experience. Can you get to the same place about all of the stuff that normally generates the sense of “I”, the sense of me, the most important creature in the universe? This is the uprooting of ignorance, and when that’s done, then the whole edifice of self/craver/clinger falls apart. Furthermore, it’s taken care of forever.

You can read the est of this chapter (chapter 3) in the original, which is a free Dhamma book, as PDF, Epub, Mobi. Look for the link in Leigh’s Website:

https://leighb.com/index2.html#RightCon

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1pZQdBy3u84

Another link from the Website, a helpful video on emptiness. At the beginning of this video, you will see he uses the acronym: SODAPI (Note: the sound of the ending of the word rhymes with ‘eye’) Streams Of Dependently Arising Processes Interacting, SODAPI

You must be logged in to post a comment.